By Scott Ronalds

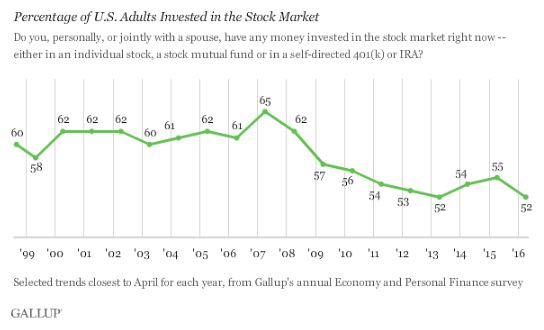

According to a recent Gallup survey, a little more than half of American adults (52%) have money invested in the stock market today (through brokerage accounts, mutual funds, ETFs or retirement accounts). On its own, this data point doesn’t mean much. But consider that less than 10 years ago, nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) had money in the market (see Bloomberg chart below). Barry Ritholtz, a U.S.-based wealth manager and Bloomberg columnist, expands on this trend of declining stock ownership in a recent article.

The decline is concerning, and reflects a growing phobia among average Americans (and Canadians) towards owning stocks in one form or another. Following the global financial crisis of 2008, the number of people owning stocks dipped meaningfully and hasn’t recovered. As Ritholtz points out in his piece, this could have real implications down the road on peoples’ standard of living in retirement.

Why the decline? A number of factors could be playing a role, but a general dislike or mistrust towards the stock market is cited by many as the biggest reason. Investors have been through a lot over the past decade and it’s wearing on people. A recent Business Insider article titled People hate the stock market, and that might not change for decades, speaks to this negative sentiment.

The market can be a scary place. Believe me, I get it. Stocks can see wild swings for reasons that seem to make no sense. The language is confusing, the product shelf is boundless, and ‘expert’ opinions run counter to one another all the time. Stocks may not elicit the same physical fear in people as other phobias, like say spiders (arachnophobia), but the lasting impact of stockphobia can be much more serious. Peoples’ long-term investment returns are at risk. This is because stocks are the engine of growth in any portfolio.

Over long periods of time, stocks provide the highest returns. The key is to make sure you’re properly diversified, keep your costs down, and stay invested (don’t try to time the market). And if you need help in getting over the phobia, keep in mind two numbers: $294,000 and $7,000. These figures represent the compound growth of a $100 investment in stocks (S&P 500) and bonds (10-year U.S. Treasury bonds), respectively, since 1928. (Note: we highlight U.S. returns because Canadian data doesn’t go back as far. Data source: New York University.)

In our view, every investor should have at least some exposure to stocks. If you’re a Steadyhand client, we make sure you have exposure (through the composition of our funds). Indeed, even our Income Fund has 25% of its assets in dividend-paying stocks, as we believe they add diversification and yield benefits to the portfolio.

How much stock should you hold in your portfolio? That’s a question we’d be happy to discuss over a phone call or a coffee. We’ll make sure there are no spiders around.

1